Turning image, turning meaning

Georg Baselitz, born in 1938 in Saxony, is one of the most provocative and consequential figures in post-war art. He works across painting, sculpture and printmaking, and his career has challenged conventions of representation, form and narrative. In this article, we explore how Baselitz’s life shaped his art, what it means to invert a motif, and why his work continues to resonate with collectors and institutions today.

Early years and formation

Baselitz grew up in Deutschbaselitz, Saxony, in the aftermath of the Second World War. His early environment was marked by destruction and instability, with much of his hometown damaged or lost. These early experiences shaped his fascination with disorder, fragmentation and recovery, which later became recurring themes in his art.

After being expelled from art school in East Berlin for what was deemed “political immaturity”, Baselitz moved to West Berlin and completed his studies in 1962. Around this time, he adopted his artist name from his birthplace, symbolising both origin and reinvention. His early paintings already reflected the turmoil of post-war Germany, blending figuration with distortion and expressive tension.

These formative years forged Baselitz’s enduring interest in disruption, both aesthetic and emotional. The sense of being caught between destruction and renewal would define his later work.

Reinventing representation through inversion

In the 1960s, Baselitz began developing his own visual language. His early paintings were emotionally charged, confronting viewers with raw human forms and distorted bodies. Works such as The Big Night Down the Drain caused controversy for their graphic and unflinching portrayal of human vulnerability.

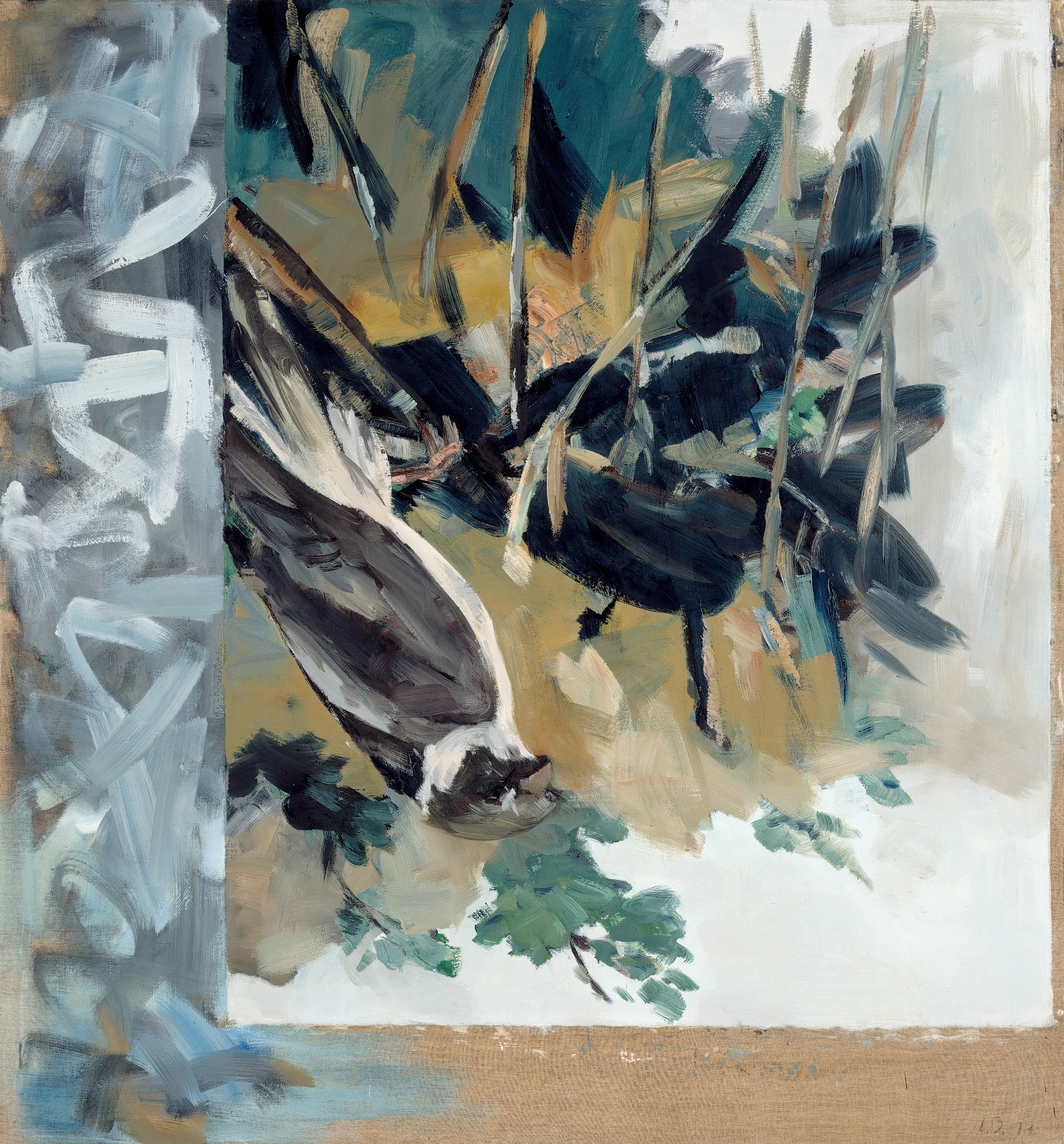

Then, in 1969, Baselitz made a radical decision that would define his artistic identity: he began painting his subjects upside down. The inversion was not a stylistic trick. Rather, it was a way of stripping away narrative, compelling viewers to see painting as painting, not as storytelling.

Through inversion, Baselitz forced an engagement with composition, brushwork and texture. The viewer had to reconsider how meaning was constructed. This simple act of turning the image on its head became a profound statement about perception itself.

He also used fracture and dislocation as compositional strategies. Figures were often split, distorted or partially erased, echoing the fractured psyche of a divided nation. Recurrent motifs such as forests, birds and limbs carried psychological depth, blending memory and mythology.

Evolution and shift in medium

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Baselitz continued to expand his visual vocabulary. He experimented with finger-painting, raw impasto and simplified figures that hovered between structure and collapse. His process was physical and instinctive, reflecting a struggle between control and chaos.

Baselitz also became an accomplished sculptor. Working with wood, he carved monumental, almost primitive forms using chainsaws and axes. These sculptures shared the same sense of disruption found in his paintings, emphasising surface, weight and the mark of the hand.

Printmaking, particularly woodcuts, became another outlet for his interest in material and gesture. Over the decades, Baselitz returned to earlier motifs in his Remix series, reinterpreting them through fresh techniques and emotional registers. More recently, he has turned to introspective themes, producing self-portraits and nude studies that reveal an artist reflecting on his legacy.

His exhibitions continue to attract major institutions worldwide, demonstrating his enduring influence on contemporary visual culture.

Legacy, market and meaning

Baselitz stands alongside Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer as a central figure in post-war German art. His influence reaches across generations of artists who engage with memory, identity and the physical act of painting.

From an investment perspective, Baselitz’s work remains a cornerstone of the blue-chip market. Paintings, sculptures and prints regularly command significant prices, reflecting both historical importance and continuing relevance. Collectors value his work for its tension between control and chaos, destruction and renewal.

Beyond financial value, Baselitz’s art speaks to broader human questions. His inverted images and fractured figures challenge us to see differently, to accept ambiguity and to find beauty in imperfection.

Conclusion

Georg Baselitz is an artist of contradictions: destructive yet restorative, expressive yet analytical, deeply personal yet historically charged. His decision to turn his images upside down was also a decision to turn meaning itself inside out.

For collectors and institutions, Baselitz represents more than a name in post-war art history. He embodies a way of seeing that remains as vital today as it was half a century ago. His work invites reflection, not only on what we see, but on how we see it.

If you are considering acquiring a work by Georg Baselitz or wish to understand how his practice aligns with your broader collecting goals, our team at Zurani can guide you. Contact us at +971 58 593 5523 or email contact@zurani.com to arrange a confidential consultation.